Navigating Necrotic Enteritis Challenges in Ostrich Chick Rearing

Enteritis is not a novel or uncommon term in the poultry industry. Enteritis refers to inflammation of the intestines which can often be followed by necrotic enteritis — an acute infection of the intestines. Necrotic enteritis (NE) is a common bacterial disease affecting poultry, including chickens, turkeys, and ostriches. Ostrich chicks are especially susceptible to gut dysbiosis, often leading to NE. Bacterial pathogens such as E. coli, Clostridium perfringens and Salmonella spp. are the key contributors to enteritis in ostrich chicks, with C. Perfringens commonly being the main culprit.

What is Clostridium perfringens?

Clostridium perfringens is a gram-positive, spore-forming, anaerobic bacterium that is widely distributed in the environment and the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and

animals. It is a common soil inhabitant and can also be found in water and decaying vegetation.

Known for producing potent toxins, it is a major cause of enteritis in animals. The spores allow it to survive in harsh conditions, including extreme heat, drought, and chemical exposure.

Gut dysbiosis and gastrointestinal diseases are the most frequent and economically important diseases in the ostrich farming industry. The majority of mortalities in ostriches occur in the first three months of age. Mortalities of 20% in ostrich chick rearing systems are considered “acceptable” and even normal. Mortality rates in practice can be well above 20%.

Necrotic Enteritis (NE) in ostrich chicks

Ostriches younger than three months of age are more sensitive to diseases of the gut, like NE, to the extent that sudden death can occur within 24 hours in some cases. The disease typically occurs when there is an overgrowth of C. perfringens in the intestine, often triggered by factors such as sudden dietary changes, handling or transport stress, dramatic changes in weather or underlying intestinal damage.

Ostrich chicks with enteritis display the following:

- Rapid drop in weight before death

- Affected chicks often stop eating and drinking

- In some cases, chicks suffered from diarrhoea

- Dehydration and loss of weight

- Extensive inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract

Figure 1: Normal intestines of an ostrich chick (control group).

Figure 2: Highly inflamed intestines with clear signs of necrosis from an ostrich chick that died from enteritis. Farmers often refer to chicks as having “Rooiderm”.

Figure 3 & 4: Further signs of hemorrhage in the front lobe of the liver can be noted, as well as yellow necrotic foci in liver.

Microbiome diversity and chick survivability

A study done in 2020 through the Western Cape Department of Agriculture on gut dysbiosis and the microflora of juvenile ostrich chicks revealed the importance of a healthy and diverse gut microbiome for healthy, fit animals.

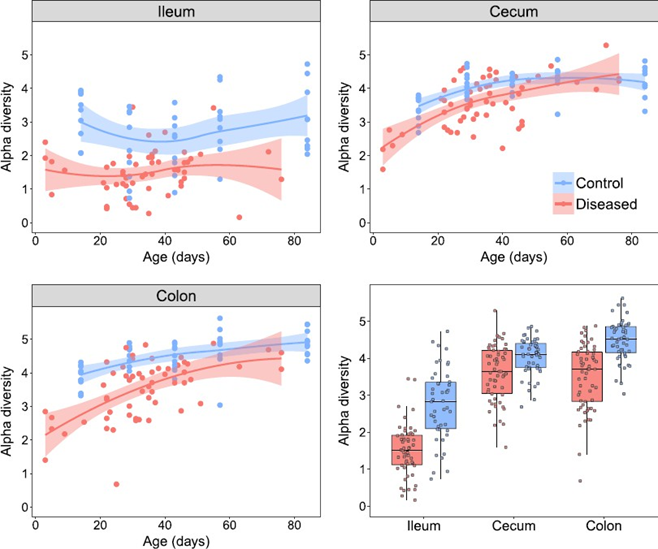

Figure 5: Effect of Age and Disease Status on Alpha Diversity Across Intestinal Regions

Figure 5 above (Source: Videvall et al. Microbiome (2020)) shows the Alpha diversity during development in the ileum, caecum, and colon. Control (healthy) birds are shown in blue and diseased birds in red.

The term Alpha diversity refers to the diversity of microbial species within a single sample or environment, such as the gut microbiome. It provides a measure of the richness (number of species) and evenness (distribution of species abundance) within a given microbiome.

The deceased chicks had greatly reduced microbial diversity in all three gut regions in comparison to the healthy control ostrich chicks. Higher alpha diversity is often associated with a healthy, more resilient gut. This is because microbial diversity indicates the stability and complexity of microbial communities, which are essential for digestion, immunity, and pathogen resistance.

What does this mean for ostrich chick management?

Considering the importance of a diverse gut microbiome for growth and survival, on-farm management should strive to preserve and improve the gut health of ostrich chicks.

In nature, a newly hatched ostrich chick acquires its microbial gut flora from its immediate surroundings that contain favourable bacteria from its mother and other adult ostriches.

Chicks reared commercially are not exposed to the same microorganisms as naturally hatched chicks and will acquire bacteria from the rearing unit surroundings instead. These chicks are also often hatched long after the natural breeding season of ostriches, exposing them to weather conditions less ideal for their health and performance.

Steps for assisting in the development of healthy gut microflora by limiting stressors:

- Newly hatched chicks are comfortable at around 26-27ºC. Fluctuating temperatures will lead to heat and cold stress. Temperature stress is believed to be a common trigger for enteritis.

- Chick housing and runs should be cleaned, dried and disinfected properly before chicks arrive.

- Ensure enough feeder space and drinking space per pen.

- Test the water sources at the start of chick season to ensure optimal water quality and avoid bacterial contamination through drinking water. Water is the most important nutrient we provide for our animals!

- Use a well-formulated starter ration to provide chicks up to 12 weeks with the correct balance of energy, protein and fiber.

- Avoid overstocking. Ostrich chicks need enough space to be active and move around comfortably.

- Provide appropriate ventilation when chicks are kept indoors. Ammonia and carbon dioxide build-up will lead to respiratory stress.

- Reserve the use of antibiotics only for sick animals. Using antibiotics prophylactically may alter the gut microbiome and kill healthy bacteria as well.

- Limit handling the chicks as much as possible. When chicks are handled, it must be done quietly and slowly - no shouting and chasing.

- Vaccination against Clostridium exists, but can be expensive and often the vaccinations are not registered for use in ostriches. Further research on the efficacy of these vaccines in juvenile ostriches needs to be done.

- There is limited evidence suggesting that including some strains of Lactobacillus in the diet up to two weeks of age can positively influence survival in ostrich chicks. Further research is needed, but the use of probiotics may have a positive effect on chick survival.

- Preventing and managing mycotoxins in feed. Mycotoxins disrupt the integrity of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and can cause leaky gut, which can be attributed to Clostridium overgrowth.

- Ensure a clear biosecurity protocol is implemented and understood by staff. This can include using clean PPE, using footbaths at each unit on the farm, and moving between houses in the correct manner (starting with the youngest and finishing with the oldest animals).

- Wild birds can also be carriers for harmful pathogens, and should not have access to chick housing if possible.

Conclusion

It is important to properly manage the things we can control. Ostrich chick rearing is largely done in open housing and paddock systems. Chicks are consequently often exposed to unpredictable and fluctuating weather conditions. It is therefore very important to provide these birds with consistency in other management aspects, like nutrition. Good feed management will help in achieving good growth rates, keep a positive balance in the animals’ gut microbiome. By using a well-formulated feed range from a trusted supplier, chicks will consistently receive a ration that contains good-quality, highly digestible ingredients.

For more information on navigating necrotic enteritis challenges in ostrich chick rearing, please contact your De Heus technical advisor - https://www.deheus.co.za/meet-our-team/.